The Bitterroot Plant

- Lewisia rediviva Pursh

- Purslane Family (Portulacaceae)

Narration:

General Information

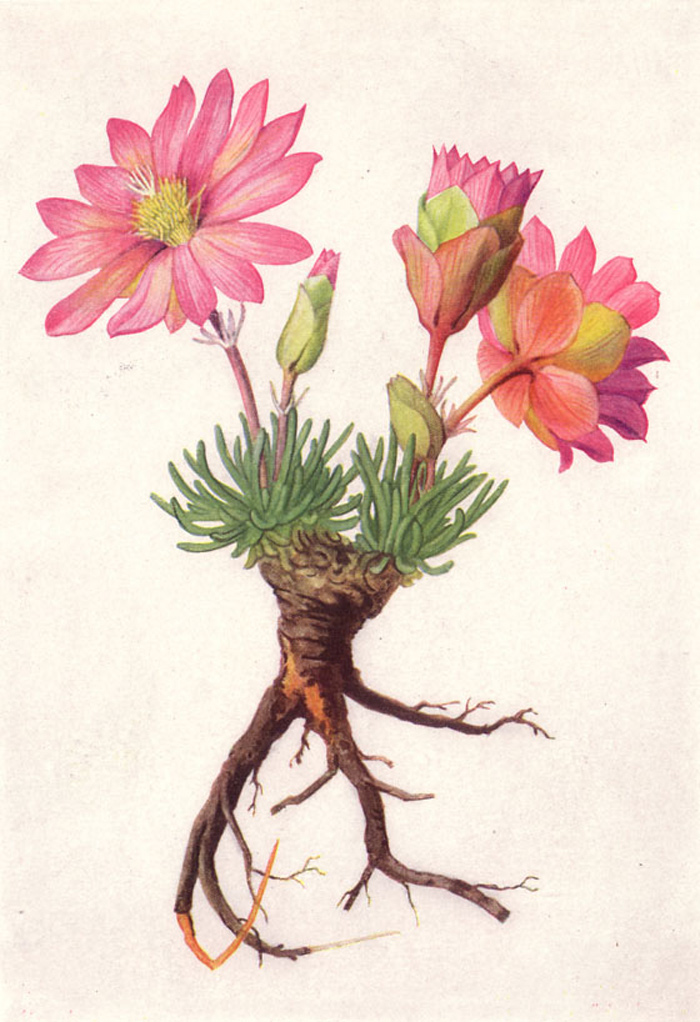

- Plants: Low-growing, perennial herbs about 2 inches tall. Leaves all basal, up to 2 inches long, narrow, round in cross-section, and fleshy. Leaves begin to wither by the time plant flowers.

- Flowers: ink, rose, or white, large and showy, solitary. Each flower has six to nine sepals, twelve to eighteen petals, many stamens, and four to eight styles.

- Fruits: One-celled capsules with six to twenty seeds each.

- Flowering Season: May to July.

- Habitat/Range: Dry, exposed, gravelly or rocky soils from the plains to lower mountain slopes of interior British Columbia, south to California, and east to Montana and Colorado.1

Blackfeet Ethnobotany*

by Darnell and Smokey Rides At The Door

The Blackfeet name of bitterroot is Aik Sik Ksi Ksi, translating to "white root." Bitterroot is exclusively found in the west, and the Blackfeet people believe that the Creator gave this plant to their people as an important plant of many uses.

From a medicinal perspective, bitterroot is considered by the Blackfeet to be healing to the whole body. By various manners and in conjunction with other plants, especially with the serviceberry, the bitterroot is particularly healing to the digestive system and respiratory system. When dried and rehydrated, as the Blackfeet often did to preserve stores of plants for the winter months, it is gelatinous and swells.

The Blackfeet people believe that the healing ability of the bitterroot is most potent around the New Year, which is traditionally celebrated at the first clap of thunder during the first rainstorm.2

From the Journals

by H. Wayne Phillips

The explorers collected a specimen of bitterroot while they were camped at “Travellers rest”, near Lolo, Montana, and the specimen still exists in the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Frederick Pursh, the botanist that Lewis hired in 1807 to work on his herbarium in Philadelphia, wrote on this specimen’s label: "The Indians eat the root of this Near Clark’s R. [Bitterroot River] Jul. 1st 1806."3

Named in honor of Meriwether Lewis, Lewisia was one of three new genera that Pursh named in his 1814 Flora Americae Septentrionalis. Pursh wrote about bitterroot in the book:

This elegant plant would be a very desirable addition to the ornamental perennials, since, if once introduced, it would be easily kept and propagated, as the following circumstance will clearly prove.

The specimen with roots taken out of the Herbarium of M. Lewis, Esq. was planted by Mr. Bernard McMahon of Philadelphia, and vegetated for more than one year: but some accident happening to it, I had not the pleasure of seeing it in flower."4

Most likely Pursh applied the epithet rediviva to this plant because of McMahon's attempt at cultivation; the Latin redivivus means "reviving from a dry state, living again."

On August 22, 1805, at Camp Fortunate, Lewis tasted bitterroot that came from "a bushel of roots of three different kinds dryed and prepared for uce," which George Drouillard had acquired in an altercation with some Shoshone Indians. Lewis wrote in his journal:

another speceis [bitterroot] was much mutilated but appeared to be fibrous; the parts were brittle, hard of the size of a small quill, cilindric and as white as snow throughout, except some small parts of the hard black rind which they had not seperated in the preperation. this the Indians with me informed were always boiled for use. I made the exprement, found that they became perfectly soft by boiling, but had a very bitter taste, which was naucious to my pallate, and I transfered them to the Indians who had eat them heartily.5

Additional Information: Today, the bitterroot is the floral emblem of Montana as well as the source of several of Montana's place names: Bitterroot Mountains, Bitterroot Valley, and Bitterroot River. As mentioned above, the species name "rediviva" is derived from the Latin word relating to revival from dryness. Seeds from the bitterroot plant can survive for years until favorable conditions are found to sprout. The plant is culturally significant to many Native tribes on the plains and in the mountains of the west.

*While traditional medicine is still practiced in many cultures including the Blackfeet culture and has many uses, please do not consume any plant material without consultation of a health professional.

© J. Brew 2008. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC-BY-SA 2.0) license.

© Matt Lavin 2009. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC-BY-SA 2.0) license.

Painting by Mary E. Eaton. This image is in the Public Domain.

© Wayne Phillips. Used by permission.

Notes

- "Lewisia rediviva Pursh," United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Plant Database, plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=LERE7.

- All ethnobotanical information was given or verified by Smokey Rides At The Door and Darnell Rides At The Door. Initial research came from Native American Ethnobotany Database. Please be advised that not all studies included are correct and to consult with Native community members to verify information.

- H. Wayne Phillips, Plants of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2003). H. Wayne Phillips graciously donated his expertise on this subject by writing this narrative.

- Frederick Pursh, Flora Americae Septentrionalis, or, A systematic arrangement and description of the plants of North America v.2 (1814).

- The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark, Gary Moulton, ed.